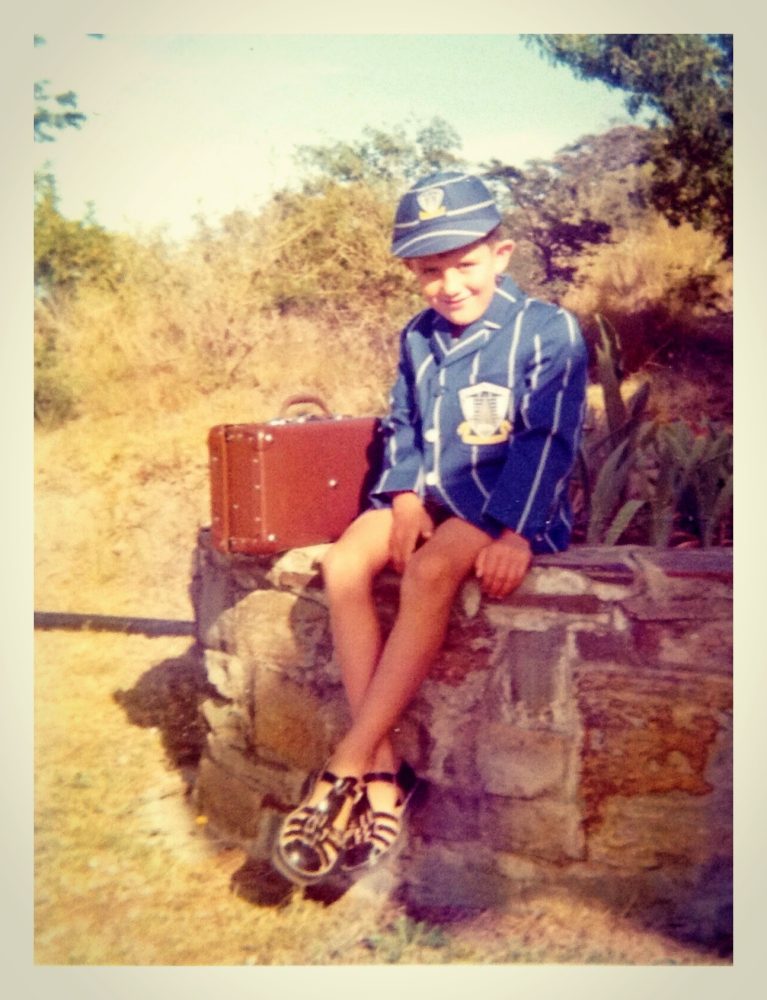

Helen E. Buckley’s poem The Little Boy is a deceptively simple parable. A small child enters school, wide-eyed and brimming with imagination. He draws with bright colours, shapes that twist and turn, images that pour out as freely as breath. Yet he quickly learns that in the classroom, his creativity is not entirely welcome.

“‘Wait,’ said the teacher. ‘It is not time to begin.’”

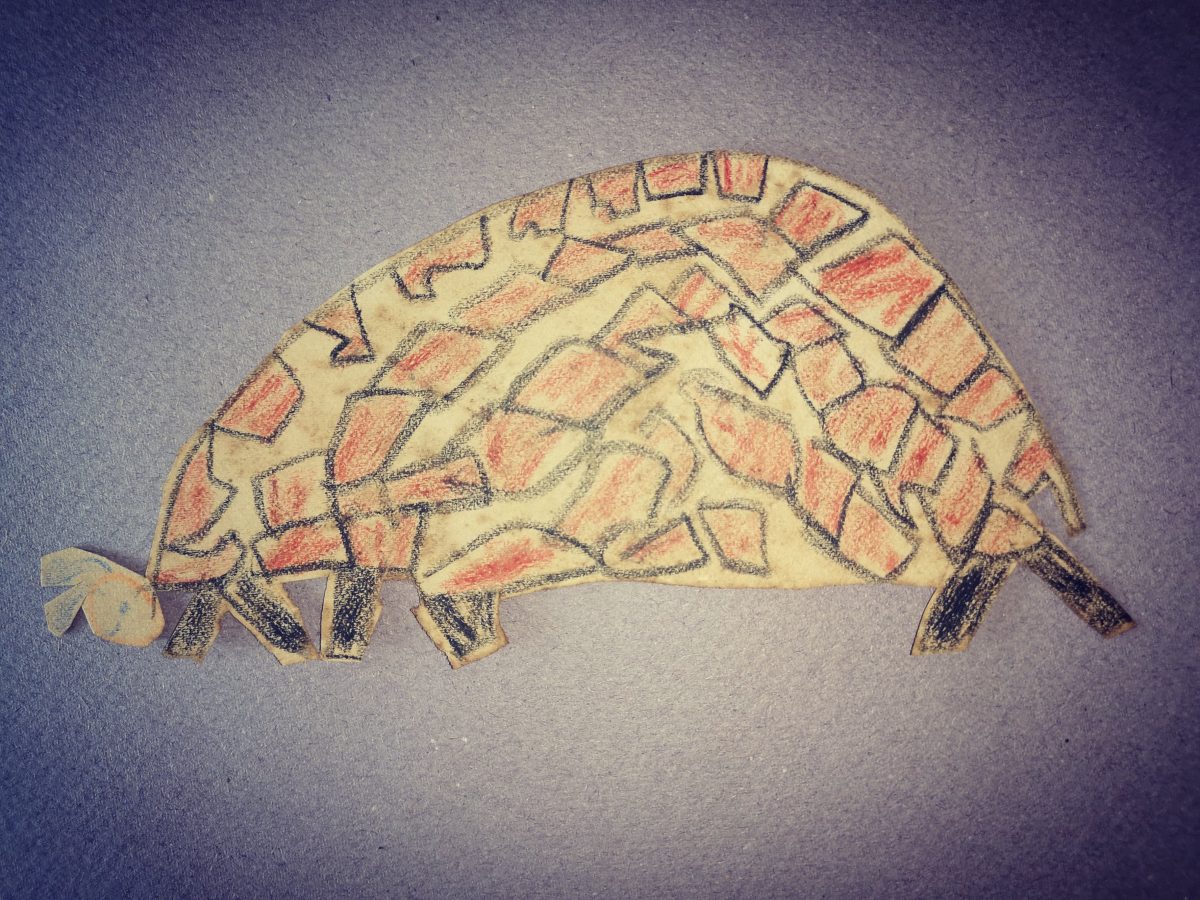

The child hesitates. He watches, and when it is his turn, he mimics. The spontaneous mark that might have been a ladybird, a cat, an owl, or a witch and her broom becomes the red flower with the green stem the teacher has prescribed.

Through these verses, Buckley captures a truth many of us recognise: our education systems, though often well-meaning, tend to prize conformity over curiosity. In wanting to guide children, they unwittingly strip away the very spark that fuels discovery. The boy, who once painted “all sorts of things,” soon learns to ask, “What do you want me to draw?”

This is not just a story of childhood; it is a story of us.

Most children begin life with a boundless sense of wonder. They notice the glimmer of light on water, the hum of a bee, the feel of soil between their fingers. They invent stories with sticks and stones, create whole worlds from shadows and clouds. It is not that children are trying to be “creative” — it is that their natural state is one of curiosity and invention.

But when the structures of schooling enter, the emphasis shifts. Instead of delighting in discovery, they are tested on recall. Instead of being encouraged to ask “Why?” they are rewarded for having the “right” answer. The result, as Buckley so poignantly shows, is a gradual narrowing of the imagination.

The tragedy is not that the child learns to draw a flower a certain way, but that he learns to distrust his own inner vision.

If you listen closely, you can hear the voice of the little boy inside many adults today. How often do we hesitate before expressing an idea, waiting for permission? How often do we temper our impulses with the silent question: “Is this what is expected of me?”

The boy in Buckley’s poem grows up, carries his box of crayons into another classroom, and waits again. “‘Show me what to do,’ he said. ‘Then I will do it.’”

The pattern repeats in our workplaces, relationships, and personal lives. We default to the safe answer, the predictable line, the sanctioned path. Yet underneath, there remains the longing to return to wonder — to the moment before the teacher said “Wait.”

If education is where creativity is often dimmed, and, crucially, when working with our young creatives, it can also be where it is rekindled. This requires a shift in how we value learning. Rather than rushing to correct, we can listen to the stories children are trying to tell through their marks and words. Rather than rewarding the perfect answer, we can celebrate the thoughtful question.

Wonder thrives where freedom and encouragement meet. It does not require elaborate resources, only space and trust. A child drawing the sun in purple or the grass in red is not wrong; they are experimenting with perspective, colour, and meaning. Each experiment is a seed of originality.

Buckley’s poem is not an indictment of teachers but a reminder that adults hold great responsibility. To honour a child’s imagination is to honour their way of seeing the world.

For adults, wonder is not lost but often buried. It flickers in moments when we pause: noticing how light shifts on a wall, tasting a new flavour, listening to birdsong. To nurture it, we must give ourselves permission to be curious again.

This can mean approaching the ordinary with fresh eyes. Take a different route on your walk. Try drawing, not to create a masterpiece but to rediscover the movement of your hand across paper. Ask “What if?” more often, even when you don’t have an answer.

In doing so, we return to the child who once knew instinctively how to play, imagine, and explore. Wonder, after all, is not the privilege of childhood but the birthright of being human.

The Little Boy reminds us that creativity withers when boxed into expectation, but it never fully disappears. It waits within us, like unopened crayons, longing for use.

To foster wonder in children, we must resist the urge to confine. To foster wonder in ourselves, we must resist the urge to conform. If we can do this, we shape a world not of uniform flowers, but of gardens filled with surprising forms and colours — a living testimony to the imagination that makes us whole.

Just as last month’s article, The Shape of Light, reflects on the play of vision and perception, Forgetting Wonder is its natural companion, a reminder that seeing is never passive. It is a creative act, born of curiosity. To keep wonder alive is to let light keep changing shape within us, so that our lives remain open to mystery, discovery, and joy.

Guy McGowan

WASA representative in Durban KwaZulu-Natal

Chairperson of North Coast Artists, KwaZulu-Natal.

Read Helen E. Buckley’s full poem The Little Boy here: https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/little-boy-2